Meet Desirae Pillay

/Desirae Pillay's daughter Savannah has autism and cerebral palsy, and this led Desirae toward a career path in Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). Based in South Africa, Desirae is a passionate voice in the country's autism community and here she reflects on her journey as a mother and advocate.

Tell us about yourself.

My name is Desirae Pillay. I am married to my best friend, Michael and we have three children. Savannah is 20 years old, Talisa is 14 years old and Eli Michael is 9 years old. Savannah is autistic, has global cerebral palsy and had a scoliosis correction.

I work as an Assistive Technology Advisor for a company, Inclusive Solutions, where our primary work is in helping professionals and families to find the right AAC tool/strategy for people with little or no functional speech. I also serve on the National Executive Committee of Autism; South Africa. I have a love for Shalom Respite and Care Centre and try to assist them by arranging their Christmas celebration for the last 2 years. I love dancing, great dinner parties with beloved family and friends, and curling up with a great book or watching a good movie.

What was the journey of your daughter's autism diagnosis, and what is the biggest lesson you learned along the way?

My daughter was only diagnosed as autistic at about 8 years old. She was diagnosed as cerebral palsied at 6 months old and the enormity and shock of that diagnosis was very difficult. I was a teenage mother who was still learning how to be responsible for myself. I had a supportive mother who helped me with Savannah. When Savannah was 3 years old I met my husband, and his attitude towards Savannah took me by surprise. Where I saw all the challenges, he saw a little girl who should have fun. His perspective and my mom’s support helped me to accept Savannah’s diagnoses.

Savannah with her dog Jaymee.

We did everything that the therapy team suggested but as Savannah grew, I kept feeling that something was amiss. I did not have the words for it but I felt that cerebral palsy did not explain everything that Savannah was. A friend loaned me a book “Simple Simon” just for inspiration. I was mesmerised by the authors’ recount of her journey as a mom to Simon who is autistic. As I turned each page, the idea began to dawn on me…Was Savannah autistic? I discussed it with her school and they agreed, that she certainly might be. Eventually, Savannah was diagnosed by a pediatric doctor through Autism; South Africa’s clinic. I was not sad. In fact, I was relieved that we finally could help Savannah in a way that was meaningful to her. The biggest lesson I learned is to trust myself in being Savannah’s mom even though I was so young.

For our readers who aren't familiar, what's AAC? And what led you to a career in assistive technology?

AAC is an acronym for Augmentative and Alternative Communication. It ranges from using photographs or pictures or symbols to make paper based communication boards or using speech output software with visual representation of words, so that a person can “speak” out loud by selecting a word. AAC includes unaided AAC; this means using signs, gestures, facial expression, verbalisation and/or vocalisations to communicate as well as aided AAC. Aided AAC includes communication boards, devices and computers.

Savannah holding on to her low tech communication tools.

This career chose me. When I first encountered AAC, I did not believe that it was something that would work for Savannah. I really did not want Savannah to communicate in a way that I considered strange. However, a friend of mine who did not know about my misunderstanding about AAC, arranged for her company to donate AAC software to us to help Savannah to communicate. Against my own ill-informed opinions, I began the journey in helping Savannah to communicate. Within a couple months, she began at least making simple choices and using a simple communication board. Within 18 months, she was using a dynamic display which no one on her therapy and education team believed that she would ever use. A speech therapist with no AAC background worked with us, and together we tried different ideas to communicate with Savannah. Our success with Savannah was so astounding to the then director of the Inclusive Solutions that she offered me a job. And that set me on a career that took me from using paper based low tech communication to help my daughter to communicate, to conducting eye tracking assessments for people who can only use their eyes to control a computer to communicate.

In South Africa, what challenges or barriers do the autism awareness and disability inclusion communities face?

Over the last 15 years of being involved in this field, I realise that the many challenges that we face in South Africa are also experienced in other countries. The stigma about disability; the outdated beliefs that people with disabilities should conform to our standards in order to be accepted; cultural beliefs that promote exclusion and devaluing a person with a disability by only recognising them as an “inspiration” or a “burden” are barriers to inclusion.

Like politics and religion, within the autism community we also have very strong opposing perspectives about supports, therapies, priorities and roles. Overall, the most difficult challenge in South Africa is the lack of resources to assist autistic people and their families, most especially in rural areas and also in lower income groups within cities. As a country there are many homes without basic services, and when a family is faced with the challenges that disability brings with it, often therapy, education and medical supports are simply unaffordable.

What advice do you have for parents raising a child who has special needs?

I had Savannah at a time when cell phones looked like bricks and Google was relatively unknown. Few people had access to the internet even in places of work and even fewer had access to computers in their homes.

Being a teenage mother with limited resources and limited access to information, I had to believe more of myself and I had to believe that Savannah had skills that needed to be "unveiled." But believing wasn’t going to be enough. I needed to also let go of my expectations, and see Savannah as a separate person with her own story to tell. That took some time for me to realise. I had to learn that while we worked at overcoming challenges together, I had to accept that what I recognised as success, may not have had any meaning to her. In turn, the things that I mourned that she may never do, were rarely ever her goals.

I would say to parents while we have to make the big decisions and have the stamina to teach and motivate over and over again; it is really important to make sure that we know whose dreams we are fighting for and to never let our emotional energy dictate our children’s emotional space.

Tough question — what's the proudest moment you have had as Savannah's mother?

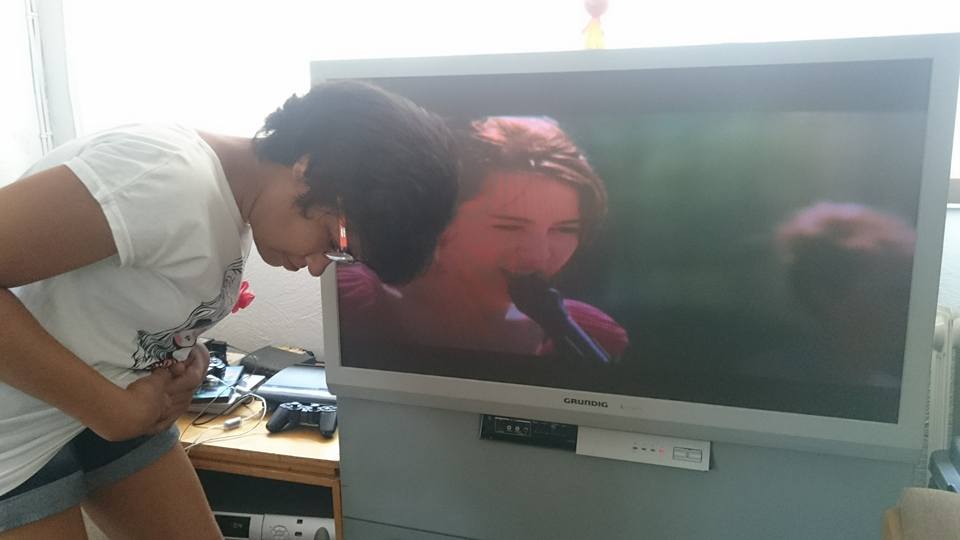

Savannah listening to the climb by miley cyrus.

It is a tough question, because there have been a few proud moments. The one that stands out is when my brother, Darren was facing the decision to amputate his leg after a motor bike accident. I was inconsolable as just a year before Savannah started using a wheelchair due to her physical challenges. I was sitting in my lounge, crying; when Savannah came to me. She always struggled to understand emotions and often laughed because of the strange facial expressions. On this day she sat next to me, rubbed my back and said “Mom, uncle D be ok.” And then she played Miley Cyrus’s song, The Climb. That day, she pulled me out of a deep dark pit of despair. This complex autistic person, with inarticulate speech, physically disabled and who will never be “fine” spoke a truth to me that I was unable to see.

Darren decided to amputate his leg, and in view of Savannah’s challenges, he is indeed “fine”. He accredits much of his positive attitude during his recovery and living as an amputee to Savannah. She makes me proud that despite all her challenges, she cares about people when she could be bemoaning her own circumstances.